The former Towanda Middle School was the scene of a shooting of a teacher on a chilly morning in 1974, when such incidents were considered isolated and mere anomalies. Far too commonplace today, school shootings leave many more victims in their wake than previously believed.

by Rick Hiduk (first posted in 2014)

Memories can last a lifetime, whether they are good or bad. “Repressed memory” is a peculiar phenomenon because it is usually, yet not always, experienced subconsciously. According to entries on the topic posted on Wikipedia, which I tend to refer to only for ideas and not for facts, the jury is still out as to how certain memories are actually suppressed or whether they are not just “conveniently” forgotten. I don’t know, as I am not a clinical psychologist, and, apparently, even Sigmund Freud waffled on his theories about repressed memories throughout his career.

A song on the radio can easily bring memories of related events back to the forefront, but were these recollections suppressed or merely shelved by our complex brains as relatively insignificant?

A vibrant color photo found in the bottom of a drawer can bring back sounds, tastes, and smells and even a little melancholy if we miss a friend or family member who is part of the recollection. Those are the good repressed memories – or “recovered” memories, as they are also known, when you suddenly relive a cherished moment.

It is human nature to prefer to recall only the good times. Psychologists often refer to this as the “selective” memory – the desire to believe that the hard times of yesterday were not as difficult as they actually were. Reality dictates that most of us balance out our memories in a manner that assures that we learn from them; good deeds lead to rewards, while bad deeds reap misfortune, etc.

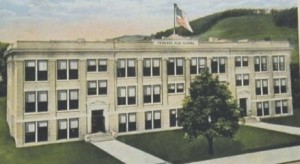

A link that a friend posted on Facebook this week sent me way back to the early 1970s, when I was a dorky sixth grader at Towanda Area Middle School (TAMS). A shooting at a middle school in Roswell, NM, left two students critically injured. Thank God this horrible ordeal did not result in immediate multiple deaths, as so many other school shootings have.

I could not bring myself to click on the link that had been emailed to me. I did not want to know the details, because I’ve been there. I’ve done that. I’m still always sickened by it. And, as much as I hope there will never be another school shooting, I have a difficult time watching new coverage of them.

In May 1992, when a former student in Olivehurst, CA, returned to his high school and shot four people to death, I was watching the event unfold on CNN. As the young man lay siege on the school, I watched the injured being escorted from the school as the shooting continued. I watched other students flee the scene, crying as they fell into the arms of teachers, friends, and waiting parents. I suddenly burst into tears.

My roommate, Nancy Faye was perplexed by what must have seemed an overreaction. I was not crying for those who were actually shot, I explained to her, as much as my heart was breaking for the witnesses, those for whom life would never be exactly the same because of the horrible things that they had seen.

Why?

The emotions that were pouring out of me were coming from my sudden vivid and previously repressed memory of a long-forgotten school shooting at Towanda Area Middle School during the 1973-74 school year, when I encountered teacher Ray Hipp as he stumbled to the concrete floor of a basement hallway after being wounded by at least one of two shotgun blasts from a weapon brought to school by a troubled eighth-grader.

A couple of days earlier, Mr. Hipp, who would eventually be the best man in his roommate’s wedding with my mother, had reportedly angered Jason, one of his students. A day or two later, Jason took a trombone case to school with him on the bus. Fellow students did think it was odd, as Jason was a not a member of the band.

He took the trombone case home and back to school the next day, according to the story in the Daily Review. That morning, he managed to find enough time alone to open the case and put the shotgun hidden inside behind about eight pieces of plywood that were stacked against the wall at the opposite end of the hallway from Ray Hipp’s homeroom. There was enough open space at the bottom to conceal the weapon.

The basement hallway under a structural addition to the old high school was known as “the tunnel” and primarily provided a passageway for boys leaving the older part of the school to the boys’ locker room under the gymnasium. There was a part-time health classroom there that was eventually was converted to a second full-time classroom (for Mrs. Bourne, an 8th-grade math teacher.)

On that day in 1974, Mr. Hipp was the lone faculty member relegated to the L-shaped subterranean thoroughfare for the entire school day, certainly an error in hindsight. The “tunnel” had a bad reputation, and any easily-intimidated student disliked walking through it. But it was a somewhat convenient bypass of the much busier first floor of the school.

It was rumored that girls had been molested there, and it was discovered by the bad boys in school that you could turn the lights off – which presumably required a key – with a fairly new dime with a good serrated edge. I was in the tunnel one day when someone turned the lights off, and there was momentary chaos in the darkness. But I did also one day turn off the lights when no-one was around just to test the “dime theory.”

The morning that Jason shot Mr. Hipp was chilly, and the landscape was still barren, so I think that it was actually late winter or early spring of 1974 – 40 years ago. I had taken to gymnastics that winter, and students were allowed to come to school early to take advantage of the gym, which was impressively set up as a gymnastics emporium.

I was a sixth grader in Mr. Curtis’s homeroom on the third floor of the former high school. I put my books and coat in my regular locker and headed downstairs to the locker room via the tunnel. As I entered the passageway from the staircase next to the office, there were two older students talking at the corner turn.

When I got about halfway down the hall, I watched Jason pull his friend closer to the stacked plywood, which was used to make a bowling alley for activities period, and say “look at this.” His friend peered behind the plywood, and then both of them glared at me as I rounded the corner.

I did not know Jason, but I knew his classmate. He was the older brother of a girl in my class and had menaced me on previous occasions. At that moment, their visual scrutiny of me was just one of many intimidating experiences that I experienced at TAMS. I proceeded to the locker room, put on my gym clothes and enjoyed my morning in the gym.

In fact, I stayed too long and had to dress quickly to get to homeroom on time. As I walked out of the locker room, I was pretty sure that I would be late, but Mr. Curtis was not such a bad-ass that he would scold me for being at school too early.

As I exited the locker room, I heard the first of two gun blasts that were aimed in my direction. There was a heavy steel door between the locker room corridor and three or four stairs up to the tunnel.

From what I recall from news reports, the first shot came from the bend in the tunnel, at least 60 yards away, and struck Mr. Hipp in the upper right leg and forearm as he stood in the corner closest to the door to his room.. The second shot hit those metal doors, hard. I don’t think that Mr. Hipp was hit by that blast, but it was the loudest noise and percussion that I had ever experienced.

Disconcerting as it was, I imagined that maybe someone had slammed shut the tunnel door ahead of me. I climbed the stairs, still worried about being late for homeroom, and pushed open the metal door to the tunnel. I got a brief glimpse of Jason as he rounded the corner, and I heard him run down the adjacent hallway.

To my left, Mr. Hipp was pulling himself to his feet and bracing himself against the wall, a look of sheer horror and specks of blood on his face. He ran into his room, slammed the door shut, leaving me alone in the hallway, and pushed the intercom button. I froze in place as I heard the distant door to a ramp leading out of the school basement close behind Jason,

“Can I help you?” the office secretary responded.

“Jason (lastname) just shot me!” Mr. Hipp shouted at the two-way speaker. “He’s running out of the school now!”

I very quickly realized what had happened, and the relevance of what I had seen and heard earlier on my way to the gym immediately struck me. I knew that Jason had shot Mr. Hipp, and I knew who the accomplice was. I also realized that, if I had opened that big steel door to the tunnel three seconds earlier, I might have been shot.

(The next morning, we read in the Daily Review that a student had come into the classroom and told Mr. Hipp that Jason wanted to talk to him outside in the hall, but the student was not named.)

Jason had run out of the building, so I did not fear him at that time. I was really still more concerned about getting to my home room…not too late. A sulfur-like odor hung in the tunnel, and two empty shotgun shells lay on the floor at the bend. I shuddered as I moved quickly past them, down the hall and up the stairs.

I figured that I was in trouble when I reached the third floor and Mr. Curtis and Mr. Dalpiaz were conversing in the otherwise empty hallway.

“You’re late.” Mr. Curtis said.

“Jason (lastname) shot Mr. Hipp in the tunnel,” I blurted out.

Mr. Curtis and Mr. Dalpiaz gave me equally skeptic, yet concerned glances and sent me into the classroom. Looking back now, I wonder if they had heard the shots.

I walked into my homeroom, sat down and told a the students seated closest to me what I’d observed. As the story started to spread across the room, the TAMS principal – probably Mr. Prettyman – announced over that intercom system, “Attention, Teachers: Please keep students in their classrooms until further notice.”

A few kids near me uttered nervous “wows,” and I looked out to the hall to see Mr. Curtis summon me with his finger. He asked me to tell him and Mr. Dalpiaz what I saw, after which I was sent back to my seat.

Because I had already told my teachers about what I had experienced, I was one of several student witnesses, including Jason’s cohort, who were called to the office to be interviewed by the state police that day. I never told them what what I actually saw earlier that morning. I’d already been warned by classmates that I’d be killed if I told the truth, and that’s something you take seriously when you are 11.

Several of my classmates immediately started calling me a “narc” and suggested that Jason would break free from prison that night and kill me because I was a witness. The lack of support and verbal harassment that would be expected of sixth graders surprisingly extended to the adults around me. Perhaps because none of us was actually struck by Jason’s shotgun blasts, they were unable to see all of us as victims.

After the crisis had ended, we eventually went to the locker room for gym class later that day, and there were still blood-stained pellet marks on the gray stuccoed walls of the tunnel near Mr. Hipp’s door.

Granted, the situation was new to everyone. But the teachers, the administrators and my own parents exhibited an apathy about it that turned my world upside down. They had no idea what I, as well as the students in Mr. Hipp’s eighth-grade homeroom experienced that day, nor did they take the time to understand, and I all but failed the sixth grade because of that and other issues.

Without so much as an assembly or a meeting with a counselor to address our feelings about the incident, we were left to accept that this was the new normal. The school shooting and the bullying of which I was often on the receiving end kept me from ever truly feeling safe at school again until I moved to Tunkhannock in 1978.

The 1974 school shooting in Towanda was unlikely the first of its kind, but it did make national news that night – reported by Walter Cronkite with a star placed approximately over Towanda on a map of Pennsylvania and northeastern United States. There was no way at that time for even the major networks to get video footage out of such a remote town in time for the 6:30 evening news.

We have come so far since 1974 in terms of safety measures that have been implemented at schools locally and across the country, especially since the Sandy Hook shootings last year. But school shootings continue.

I can only hope that there is much more counseling and support for students or anybody affected by such senseless acts of violence. If not, all of the images and feelings associated with the event may be “forgotten” but will continue to shape the observer’s life.

It would be nice to know that Jason at least got the counseling that he needed before and after the time that he reportedly spent in a juvenile detention facility. I have no idea where he was sent nor where he has lived as an adult, but I hope that his transgressions as a teenager did not prevent him from enjoying a productive life and raising a family. I also do not know what happened to his accomplice, as he was not pictured in the 1977 Towanda High School yearbook when he would have presumably been a junior. Ray Hipp eventually retired in the Altoona area, which is where he was from.

For me, just having those repressed memories of the awful school day in 1974 burst out of me 18 years later did help me begin a self-healing process that I never knew I needed. I have never dreamed about the shooting itself, but I do occasionally dream about people shooting at me, and there is a (legal) gun behind every bedroom door in my home, so maybe it haunts me yet.

But I fear even more that we as a nation might someday become as jaded to gun violence as people in war-torn areas become jaded to car bombings. We need to work harder to keep guns out of the hands of the wrong people, and we need to ensure that victims, including witnesses, get the attention they deserve and need.

Thanks for this. I was looking for some info on it as Ray Hipp is my father.

Hi, Bart. I’d really like to talk to you. Are you on Facebook?

I’m not on facebook, but I do have linkedin, twitter, OR google hangouts if you received my email address via the comment submission!

My dad was in school at the time and I told kids at the high school about it but they dint believe me now tomorrow I am going to prove it

I was in that classroom. I talked to Jason that morning because I saw the suitcase and thought he was going to run away. I told him that would be foolish. There was another reason for his actions, unfortunately Mr. Hipp was the person he took it out on. When the shots came, I thought it was a slamming door. We had heard Mr. Hipp shout Jason’s name. Actually, Mr Hipp held the door shut to prevent Jason from coming in. He didn’t know if he’d come back. He shouted for us to call the office. He was obviously bleeding. One of us pushed the intercom and when the secretary answered we shouted that Jason had shot Mr. Hipp. She made us repeat that because she was shocked. He then repeated it. I remember looking up and seeing Jason running across the parking lot. I don’t remember anything after that.