In 1778, major Native American villages existed at Tioga Point – present day Athens – and along the river bank on the far shore of the Chemung River (top) – present day Milan. Students and faculty from Binghamton University have begun an exciting archaeological project at Esther’s Flats on the west shore of the Chemung River that will last several years.

Photos and Story by Rick Hiduk

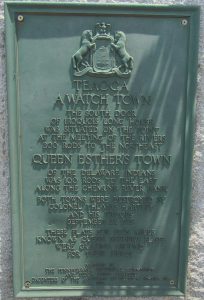

When Gens. Sullivan and Clinton began the campaign to push the Indians from northern Pennsylvania and New York state, they encountered virtually no resistance until they converged on what would eventually become northern Bradford County. There, two towns established by Native Americans still flourished: Teaoga, the southern door of the Iroquois Nation, strategically located at the confluence of the Chemung and North Branch Susquehanna Rivers; and Queen Esther’s Town, a cattle ranch and village on the west shore of the Chemung, opposite Teaoga.

It was Col. Thomas Hartley’s troops that are credited with destroying both communities on Sept. 27, 1778, after earlier being ambushed by Queen Esther’s warriors when a shower of arrows rained down upon them from the hillside along Wolcott Creek. The combined Colonial forces would continue to drive the natives north and west into Canada while burning their crops and villages to the ground, leaving many of them into starve that winter when the British could not accommodate them.

Queen Esther was renowned as a rare female leader of her era, even among Native Americans, who often involved women in governance though men served as chiefs. Half French and half Huron, Esther took control of her husband’s clan of Delaware Monsees after his death around 1772. Her village reportedly boasted about 70 huts, her “castle,” and grazing fields. She enjoyed wearing flashy clothing with glittering ornaments, which even her warriors adopted as part of their uniforms.

They were certainly not the first inhabitants of the fertile flood plains, Dr. Nina Versaggi, director of Binghamton University’s Public Archeology Facility points out. “There had been Native Americans there for thousands of years.”

Esther was apparently courteous and friendly to strangers unless one evoked her ire. This happened earlier in 1778 when her son was killed by white settlers. It was her warriors, with the support of Tories and other British Loyalists, who floated down river to attack Fort Wyoming near present day Wilkes-Barre. The killing and brutal tortures of white settlers there, some of it reportedly at Esther’s own hands, was too much for Gen. George Washington to tolerate.

He subsequently composed the orders to Gens. Sullivan and Clinton to not only retaliate but to annihilate the Indians and ensure that they would never again inhabit northern Pennsylvania or the southern tier of upstate New York. Only when the Indian threat was officially brought to an end would white settlers be able to establish permanent communities in the northern tier of Pennsylvania. The soldiers built a fortress at Teaogo, which they called Fort Tioga.

Historical accounts vary as to whether Queen Esther survived the raids or if she lived her final years peacefully among the Cayugas. But her legacy, a balance of fact and mythology, has actually grown in recent years. In 2014, the Archaeological Conservancy (TAC) purchased 92 acres of land near the village of Milan in Athens Township commonly know as Esther’s Flats. Since 1980, the TAC has acquired and preserved 500 sites in 43 states.

In partnership with the TAC, faculty and students from Binghamton University have begun a multi-year research project to learn more about Queen Esther’s clan and their relationships with other Native Americans and the non-Natives around them. Through a combination of geophysical (non-invasive) surveys and controlled archaeological digs, they hope to determine the precise location of the town. They will be working with local historians and Native American groups who may have descended from the town’s inhabitants.

Key participants in the project include Versaggi, assistant anthropology professor Siobhan Hart, graduate assistants Amber Laubach and Katie Seeber, and numerous students. The project has begun at the northern end of the 92-acre tract and will continue through the middle and southern portions of the preserve.

In February, the school’s Freshman Research Immersion class began the geophysical work, utilizing magnetometers, electrical resistance meters and a drone to detect soil anomalies “The drone gave us a very detailed model of the high points and the dips,” said Versaggi. On May 30, she escorted students from the university’s Anthropology Department’s archaeology field methods class to the site.

“These are the students who are going to test those soil anomalies and tell us what they are,” Versaggi explained. “Sometimes, they are just nails and bolts. Sometimes, they are clusters of rocks that may be significant.” In a best case scenario, she continued, “they lead us to pots and cooking pits where Queen Esther’s people might have lived.”

On June 12, Binghamton University students (above) were escorted to the Tioga Point Museum by Laubach and Seeber, where they were shown artifacts (below) found on Esther’s Flats by museum director Todd Babcock that are part of the museum’s private collection.

“Museum’s like that are lucky enough to have local landowners donate collections like that who know exactly where they came from,” Versaggi related. “We’re confident that they are from the right time period to be from Queen Esther’s Town.”

Versaggi described the first year of the project as an exploratory season. “We hope to find Queen Esther’s Town, or it might have been where she raised her cattle.”

The faculty is confident that the students will produce a study of significant value to historians and the public. “This is probably the best group of students that we’ve had. They are an incredibly attentive, alert, and enthusiastic group,” said Versaggi. Contrary to what older people might think of today’s young adults, “they put their cell phones away and have their gloves on and trowels in their hands to discover what is hidden under the ground there.”

The site is inaccessible to the public due to the sensitive nature of exploration and preservation. Farmers currently leasing the land will continue to grow crops there until the dig is complete.